We Have To Mention The War

“Everybody has heard of the Vietnam War, right?” asks Mickie the tour guide as the minibus heads towards the tunnels.

“Well”, he continues, “let me tell you there is no such thing. My country has a history of a thousand years of war. After World War 2 we have the Indochina War, the French War, and then, the one you call the Vietnam War”, he pauses for effect, “we call the American War, not the Vietnam War. I hope before you leave Vietnam, you will understand more about the American War”.

Mickie is impassioned, proud of his country, and – like every single Vietnamese – from a family devastated by wartime killings. We do, as he hoped, learn more about the American war.

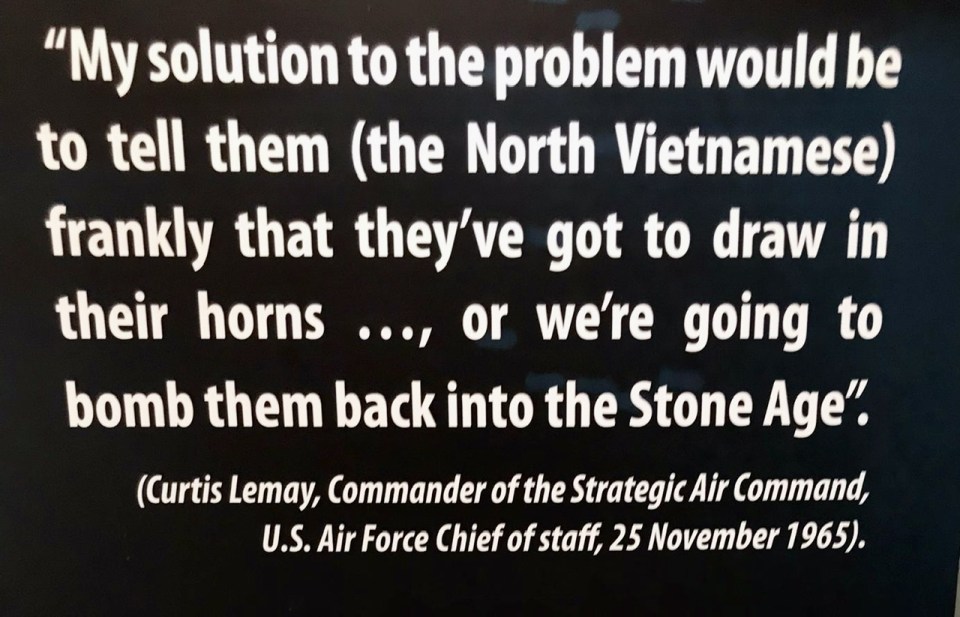

In the centre of Saigon is the War Remnants Museum, and, speaking as people who have visited Auschwitz, KGB prisons and the like, this is one of the most disturbing, harrowing, tear-jerking places we have ever visited. We’re not even sure we can write about it any detail. Our eyes sting with tears as we read of children who were mercilessly slain as harmless villages were wiped out, our brains recoil as we read of the methods of torture inflicted on ordinary civilians, of the inhumane brutality, of the wanton destruction of lives and livelihoods. Maybe just read this…

This is the closest any museum has ever come to bringing me to my knees. I briefly contemplate kneeling down and hiding my face before I manage to gather myself and carry on. How can human beings do these things to other human beings. And this is America. In my lifetime, in my memory.

Michaela and I look at each other, and she looks as drained as I feel. Then upstairs on the next floor, a section on Agent Orange, the appalling dioxin which the US dropped across vast areas of Vietnam. Its deplorable objective was defoliation: strip all plants of life and the population will starve. That’s exactly what it did: everything died. Crops, trees, fruit trees, palms, all became lifeless stumps. If that objective alone is horrifying, then the other effects of Agent Orange are heartbreaking: horrifically damaged bodies, but with the lasting punishment of genetic mutation. Children of those who inhaled Agent Orange were born with horrific deformities, and it didn’t stop there – their children, the grandchildren of those infected, were also born with similar mutations. Chemical warfare with horrifying consequences for three generations of innocent people. If that’s not a war crime then we don’t know what is.

Even now, some 2,000 FOURTH generation babies have similarly borne the scars, and babies are still being born with the impossible, heartbreaking consequences of this terrible, terrible campaign.

I don’t even know what to say as we walk away from the museum. We walk silently across the park. I don’t think we will ever forget what we’ve just read, and what we’ve just seen. Mickie had told us that if we have a heart, we will cry while we learn about the “American War”. It doesn’t need to be too big a heart, so harrowing is the detail. And, yes, we cry.

Our excursion under Mickie’s guidance is more light hearted than the museum though, if indeed this is a subject one can ever be light hearted about. The tunnels in question are the Cu Chi Tunnels, roughly 90 minutes on the minibus out of Saigon and right out into what were the brutal battlefields of the “American” war. This is the site where the under-equipped and outnumbered Viet Cong fighters held out against major onslaughts from the US – outnumbered but not outwitted, fighting on terrain which they understood so much better than their opponents.

An entire network of thousands of miles of underground tunnels and bunkers enabled the guerillas to not only conceal themselves from the enemy, but also to spring surprise attacks. Life went on in these underground chambers as the aerial bombardment, no matter how sustained, failed to defeat those living below ground. As well as the tunnels, tiny hiding places from where the agile Viet Cong were able to pop up, shoot to kill, and then vanish. Michaela disappeared into one such hiding place….

We crawl through a long stretch of tiny, cramped tunnel – only when we are congratulated by Mickie at the far end does he tell us that very few visitors make it through the entire length without opting for one of the escape routes for one reason or another. We can well understand that – to do it you need to be bodily flexible, not suffer claustrophobia and not be freaked out by darkness. It seems a long time before we reach daylight, but we feel good that we both made it through.

For an extra fee we get the opportunity to fire AK47 rifles, missing the target on every occasion but enjoying the experience nonetheless, before being shown in graphic detail the booby traps which the Viet Cong created to intercept advancing GI’s. The traps are pretty gruesome, and almost always fatal, designed to inflict yet more damage to the body if the victim tries to wriggle free.

To resist a better equipped army with greater manpower, the Viet Cong needed to be ingenious, and ingenious they certainly were. As well as the tunnels and hidey holes, the metal spikes inside the booby traps were fashioned from American bombs and tanks, gunpowder from unexploded bombs was recycled and used against the enemy, GI uniforms buried in the undergrowth to confuse the sniffer dogs seeking those hiding in the tunnels.

Cu Chi was a battleground in every sense, crucial to Viet Cong survival and pivotal to the outcome of this senseless war. “We fought hard”, explains Mickie, “because we knew that if we lost Cu Chi, we lost our country”.

Back at the War Remnants Museum, one section focuses on the last days of the conflict, as the US and Vietnam sought a final agreement in Paris. With talks heading towards a solution considered less than perfect by the Americans, negotiations collapsed and, in a final show of brute force intended to strengthen America’s position at the table, Richard Nixon ordered the biggest bombardment of the entire conflict, dropping over 100,000 tons of bombs on target cities in a 12-day offensive known as Operation Linebacker II.

Startling Vietnamese resilience repelled the attack, a victory which was nicknamed “Dien Bien Phu in the air”, citing the name of a victory over the French 20 years earlier. During this final battle, 34 American B-52 bombers, thought to be virtually impregnable, were brought down by fighters on the ground. The terrible war was finally over. We all know the outcome.

In Cu Chi, only 4,000 of the 16,000 underground dwellers came out alive at the end of the conflict, the greater number having been killed by malaria rather than enemy fire.

Mickie has been upbeat, forthright, he’s been passionate and informative. He’s spoken of atrocities without bitterness, of his country with enormous pride.

He bids farewell by telling us to enjoy and make the most of Saigon. “We have seen enough horror and now we have the greatest city in the world. I hope you leave here with good memories”.

23 Comments

wetanddustyroads

For me it remains difficult to comprehend that humanity can be so cruel. What else is there to say about a war?

Andrew Petcher

Man’s inhumanity to man. Ever so, ever will be.

Phil & Michaela

Indeed

Suzanne@PictureRetirement

It is a part of history and can’t be ignored. Sad as it is.

mochatruffalo

Wars are always unnecessary and senseless. Millions suffer all because of the decisions of a few.

Nemorino

Good that you went to the museum and the Cu Chi tunnels. I went there in 1995, and realized that Cu Chi was only about thirty km away from Tan Ba, where I was stationed for several months in 1964/65.

https://operasandcycling.com/tay-ninh-and-cu-chi-1995/

(On many of my posts, including this one, the like button and the comment box are currently failing to load. I’m trying to fix this, with the help of a lady from Jetpack support.)

Monkey's Tale

We visited museums and sites in Laos that brought about the same emotions. Laos is another forgotten victim in the American war. Such atrocities need to be remembered and maybe one day they will cease. Maggie

Phil & Michaela

Yes we were in Laos 3 years ago and read lots, and visited places, learning things that were truly shocking. Especially when Laos itself has never been at war.

WanderingCanadians

It’s interesting to hear about the Vietnam or rather American War from a different perspective. It’s always shocking to hear what humans are capable of sometimes. It’s neat that you got to crawl through some of the tunnels and check out a few of the hiding places.

Phil & Michaela

The museum is a disturbing place to visit, that’s for sure

Toonsarah

It was the Agent Orange section of the museum I found the most horrific, but I confess we didn’t look at everything there. The displays about the anti-war protests in the US and Europe were easier to view and fascinating for someone of my generation, as I remembered them clearly. It was interesting to read about them from the Vietnamese perspective of course.

I bottled the tunnels because of the need to stoop – I knew my back wouldn’t thank me for it.

Phil & Michaela

It was mostly too tight to stoop and was a hands and knees job! Enjoy Tirana. Our Albania tour a few years ago ended up with a few days in Tirana, it’s very different from the rest of the country.

leightontravels

Yeah the War Remnants Museum is something that never leaves you. I will never forget a bunch of shithead teenagers laughing amongst each other as they were looking through the photo boards of horribly disfigured children, victims of Agent Orange. I was absolutely furious with them and was actually tempted to slap one of them in the face. I don’t think I have ever been so depressed and then so venomously angry in the same moment. Do they still display that old sewer pipe with the story of Bob Kerrey and his team of navy SEALs at the massacre of Thanh Phong village? That whole story made my blood go cold. Didn’t do the tunnels, looks pretty hairy!

Phil & Michaela

I would have hated those teenagers too. Yes the Kerrey story is there, and there are others even more horrifying which we opted not to detail in the post as just too gruesome. Suffice to say it involved children. By the way, we’re in Siem Reap now so feel free to remind me of a few if your cafe/restaurant recommendations!

leightontravels

Not sure how long you’re in town for but I’d start with Wild Bar at the top of the list.

Phil & Michaela

Ah yes I remember your post about Wild Bar now, and it’s in the very part f town where we’re heading tonight so it could well be on today’s agenda. We arrived here Tuesday afternoon and leave Tuesday morning.

Lookoom

The Vietnam wars were atrocious, on both sides. And all this to achieve a one-party dictatorship!

Phil & Michaela

Yes. A pointless war and a failure of an outcome.

Alison

Truly horrendous as you say. Words can’t comprehend the horrors inflicted by humans on other humans.

Congratulations on getting through the tunnels, Laurence got stuck half in and half when he tried ten years ago.

Phil & Michaela

😂😂

Latitude Adjustment: A Tale of Two Wanderers

It was a horrific and embarrassing American war that should of never happened. White men in power caused this. Interesting facts from both side: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Linebacker_II

Who knows what some of the truth is lost or un said. If women were leaders back then this would of never happened! Its good you posted this. Thank you!

Phil & Michaela

Possibly the most needless war in history, especially given the final outcome. If only…if only…humanity learnt from its mistakes.

Mike and Kellye Hefner

All war is pretty senseless in this day and age. We need these museums to show what really happened so it doesn’t happen again. Sadly, humans are the cruelest animals on earth.