Vietnam 2023

Hanoi Revisited: Early Days In Vietnam

It’s funny how things even up in the end. After the tortuous India-Nepal border crossing, entering Vietnam is a dream. Our 4-and-a-bit hour flight from Delhi leaves before midnight and lands 5am local time, and at Hanoi we hit an empty airport, a passport check that takes thirty seconds, and a computer system which knows we already have our visas sorted. A matter of minutes later, we’ve bought and activated a Viettel SIM card, grabbed 3 million dong from the ATM (no really) and are on our way into the city.

“Massage massage” call various tiny ladies on even tinier plastic stools outside each of the parlours in the tight streets by our Hanoi base. “Massage Sir very good price”, “massage Ma’am very good price”. As it happens I have a troublesome shoulder which is threatening to involve my neck in the circle of pain so I may well select which of those ladies is best equipped for the job later.

Whenever we visit a former prison or POW camp or similar – and don’t forget we’ve visited Auschwitz, the Death Railway at Kanchanburi and a former KGB prison amongst others – we are always left with two dominant thoughts: on the one hand, the astonishing brutality with which the human race is capable of treating his fellow man, and on the other, the amazing resilience and survival instinct shown by those trapped in the most appalling form of captivity.

Hoa Lo brings out those emotions. Dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton” by captured American airmen during the Vietnam war, Hoa Lo is now a museum and exhibition dedicated to its own history. Prior to French occupation in 1887, the land now occupied by Hoa Lo housed the village of Phu Khanh, renowned for skilled production of pots and pans. The entire village and its trades were obliterated by the French in order to build a detention centre for Communist and other political dissidents.

Throughout the period of French occupation the brutality endured with incarcerated activists forced to suffer the ultimate depths of depravity and dehumanisation. Shackled in cages for weeks on end, deprived of food and water, beaten daily, left naked for several days outside under a blazing sun, even amputation of limbs for identified ringleaders. Female prisoners weren’t spared the brutality either, with up to 300 women crammed into 4 small cells with a cup of water each per day for washing and one single bucket in each cell for toilet purposes.

Later, when the Americans came in, Hao Lo housed first Vietnamese POWs and then the Americans themselves as the balance of power shifted in Hanoi. The museum tells, by contrast to its other stories, of the humane treatment of Americans, and shows photographs of hearty meals and Christmas parties: whether this is truth or propaganda is a matter for conjecture, but it’s fair to say that such museums rarely contain admissions of brutality by the host nation…do they.

Central to Hanoi is Hoan Kiem Lake, a haven of calm in the middle of the city on the cusp of the verve of the old town district. Its calm waters wallow beneath overhanging trees as joggers negotiate its perimeter and people of all ages utilise its slightly clearer air in which to take various forms of exercise. The lake is a magnet: no matter where you wander in the city, you will at some point gravitate to its edge and soak up its peace.

Its quaint bridge leading to its humble but well adorned temple, The Huc Bridge and Ngoc Son Temple respectively, add a deep red colour under the colourless skies which seem to be an ongoing feature of Hanoi, a light grey cloak which doesn’t turn blue even when the sun breaks through. Hoan Kiem, like many lakes worldwide, is home to its own legend, which boasts such unlikely characters as a Golden Turtle God (Kim Qui), a Dragon King (Long Vuong), a courageous emperor and a sword with magical powers. Based on truth, clearly.

Enclaves of tranquility lie elsewhere in the city too, none more peaceful than a small garden across the road from the Temple Of Literature where timber houses rebuilt in the original Hanoi style circle the smaller lake, a great little corner in which to sip the delicious milk from a king coconut. The Temple itself, Van Mieu, a seat of learning dedicated to Confucius, became Vietnam’s first national university and at one time housed a school attended exclusively by the children of nobility. Although several restoration projects have been completed over the years, it is nevertheless remarkable that this place has survived the wars and disasters of the centuries.

Across the city and on the other side of the famed railway line is the bloated complex which is the mausoleum of Ho Chi Minh, so loved by his country that he is still referred to as Uncle Ho. Aside from presiding over post-WWII Vietnam for 24 years, Uncle Ho wrote books and poems in three languages and has an early history which leaves researchers and historians in confused disagreement: he is rumoured to have used up to 200 false names and created numerous different personal histories. He is also believed to have lived in West Ealing (London) for around six years and worked on the Newhaven to Dieppe ferry as a chef – all this coming before running his country, obviously.

Minh didn’t live to see the final unification of Vietnam in 1975 but his roles in fighting for independence and political ideology are clearly remembered with affection and reverence.

We file with hundreds of others through the strictly controlled mausoleum and past his embalmed and encased body as dozens of schools give their kids a day out to come see the nation’s father – or uncle – despite the fact that Ho Chi Minh himself had specifically requested to be cremated and moreover that no mausoleum should be built in his honour. Strange that such a revered and powerful individual should have his final request denied.

(Note: the frivolous part of my brain keeps wondering if his colleagues used to come into the office each day and say “Hi Ho”. I know I would have done).

Hanoi’s Bia Hoi ritual takes place daily – Bia Hoi is a beer which doesn’t have a shelf life. It’s brewed overnight, rushed out to the bars by lunchtime, and drunk in large quantities by locals and visitors alike, through afternoon and evening, until it’s all gone – after which the brewery night shift resumes and the whole 24-hour cycle starts again. The entire pageant is a pretty unique ritual made even more amusing by the hundreds of tiny plastic chairs which are thrown out in to the streets to give the imbibers somewhere to perch while downing the golden liquid.

Hanoi’s old town comes alive at night like a sanitised version of Bangkok. Little wonder that Hanoi is on the backpacker trail: beer rituals, plentiful bars, tons of accommodation, street food and bouncing night life, all at a fraction of the cost most visitors would pay at home. On one level it sounds an unauthentic nightmare; in reality it’s good humoured, unabashed fun where the split of locals and visitors is roughly 50/50 and people from around the world mix and relax.

In normal circumstances, daytime Hanoi would have the feel of a busy city, but coming immediately after Delhi even the old town feels almost serene. It is so different here: in an Indian city, one is engulfed and swallowed up by Indian culture meaning that the feeling of being in a tiny minority is inescapable. It’s easy to feel like an intruder. Here in Hanoi though, visitors from around the globe are evident everywhere: travellers and backpackers of all ages enjoying the many eateries and coffee bars which give Hanoi an infinitely more accessible character.

Reconciling modern day Hanoi with its dark and troubled history, dovetailing its one party politics with its open attitudes, explaining the proximity of night life to a museum like Hoa Lo, are diverse stories too complex to explain after just a few days. It would, we think, take a longer stay to get some perspective on those anomalies.

For us, the ghosts of our “COVID visit” have been laid quickly and our bad memories are now forever supplanted by good ones. Oh and we had a massage too. Very good price.

Halong Bay

Sunshine greets us in Halong Bay and even that one simple fact is different from the miserable days when we bowled up here before, with the world starting to close borders and the grip of a pandemic stretching its dirty fingers everywhere. Back then, this entire place was a ghost town, just us two and a handful of others about to start the mad dash home.

It was a hazy grey that day with a mist hugging the silent sea and all the tour boats waiting forlornly at anchor. Vietnam was already shutting down and tourist spots like Halong (or Ha Long) Bay had been among the first to have its doors closed by Government. It was desperate and desolate and we couldn’t get our heads round what was happening; the cloying grey mist was fittingly depressing.

Today is incomparable with that dark memory; not only does the sun shine but the harbour positively buzzes with activity as hundreds of trippers arrive to be shepherded to the various departure points for the cruise boats all chugging noisily on the water. The highway from Hanoi had been a racetrack of “limousine buses” winging their way from the capital to the sea. It’s hard to imagine a scene more different from those collapsing days of March 2020.

So here we are on board the Halong Aquamarine for a 3-day 2-night exploration of this famous yet incredible scenery. Yep, no sooner are we off the Buddha Train and relishing our renewed freedom and we go and trap ourselves on a boat – but hey, it’s only 3 (well, 2 and a half in reality) days and Halong Bay is of course on our wish list like it’s on everyone’s.

First, the good bits. Our room on board is luxurious and affords fabulous views of the islands through huge panoramic windows. Halong Bay is every bit as spectacular as all the hype and all the hundreds of photos we’ve all seen on line – truly one of the World’s most amazing natural sights. More of that shortly.

Second, the not quite so good bits. The sea here is not in a good state: never mind the floating rainbows which indicate oil or diesel in the water, but the amount of plastic and other rubbish trapped in the becalmed areas between the islands is painful to see. A UNESCO World Heritage Site with a floating garbage tip: something is terribly wrong. It’s very, very busy too: well over 100 cruise boats ply these waters daily, terrific for an economy decimated by COVID but not so good for anyone seeking an escape.

Our time out here includes kayaking to islands, through caves and out into seas hidden in the heart of sunken islands, which is absolutely thrilling and probably our most enjoyable kayaking experience to date. There’s a couple of hikes up to the summit of islands too, as well as a walk through the massive caves at Sung Sot Island, though these are slow paced due to the amount of people climbing the same trails. As we squeeze through the narrow entrance to Sung Sot cave, we have no inkling of its size: the interior is a gigantic space filled with spectacular rock formations in which the wave lines of the sea, formed millions of years ago, are clearly visible above our heads on the roof of the cave.

There are a couple of beach/swimming opportunities too, but the sea is cold, and with all that evidence of pollution staring us in the face, it isn’t in the least inviting. Also on the agenda is a visit to a pearl farm, similar in appearance to the oyster beds close to our home in England but with a very different aim: jewellery rather than food. The farm is much more interesting than we anticipated, with a decent introduction to the whole process of cultivating pearls, a hit-and-miss affair with only 30% of implanted impurities turning into anything useful – and even fewer forming the perfect sphere.

The karst limestone islands which give Halong Bay its well known and spectacular look are a fantastic sight, huge pedestals of almost vertical rock pushing up through the water and towering above us like so many petrified giants. There are something like 3,000 of these islets in and around Halong Bay, created by formation and then erosion of limestone and shaped over millennia, in turn beneath the deep ocean and exposed to the air. The whole place is a remarkable sight.

Whether motoring past on the main cruise boat, gliding through by kayak or being taken through on a bamboo boat, these tree-clad limestone marvels are endlessly captivating, their different shapes and sizes peppered with cave entrances, sculpted erosion and dramatic overhangs. Out at Lan Ha, further out than where the day trips go and consequently a little quieter, the mist starts to descend and adds an eeriness to an already haunting scene.

Many of the cruises are in fact those single-day excursions, leaving around 20 craft to anchor overnight out in the open waters of the bay. After dark, the ones overnighting collect in a stretch of water nicknamed the “sleeping area”, encircled by lofty karst islands – the lights of the vessels creating quite a pleasant scene reflecting in the rippling waves. Day trippers gone, the evenings are relatively serene. During the day though, the large numbers of visitors being ferried to the same activities and destinations creates an overload at each point of bottleneck. It is, as we said earlier, very, very busy.

Halong Bay is well and truly up and running again after the economic horrors of the pandemic, and we certainly don’t begrudge them making the most of it and pulling in the crowds. There’s been no Government handouts here, these guys have had nothing for more than two years. The unshakeable beaming smile of those employed on the boats tells its own story.

For us, we’ve at last seen Halong Bay properly, almost exactly three years since those improbable days of early pandemic and the threat of quarantine. Our ghosts are laid.

Halong Bay-Hanoi-Tam Coc: Towards Stunning Scenery

The look and sound of a wet road and the repetitive whine of windscreen wipers are inextricably linked to my memories of childhood Saturdays, and as we make our way back to Hanoi from Halong Bay in the “limousine bus” this particular Saturday is doing its best to trigger those memories. We knew to expect inclement weather during this spell, it’s that time of year here in the north.

No visit to Hanoi is complete without a trip to Train Street, so, given that we are passing back through the city at a weekend when there are more trains scheduled than at other times, we play the game of grabbing a seat at a trackside cafe, ordering a couple of beers and waiting for the thrill. Our timing is good and we don’t have to wait long: two trains in the first half hour.

How strange this whole thing is, the hulking trains rumbling through within inches of both us and the cafes and shops. As the warning comes and the train approaches, shopkeepers wind in the awnings and remove displays, cafe owners reposition tables and chairs and parents call the children indoors – all to avoid anything being struck by the train as it passes through the tight space. For visitors like us, it’s then quite exhilarating as it roars right past, so close. Time was, before Hanoi latched on to the tourist opportunity of Train Street and opened up the cafes, these buildings were simple family dwellings tight up against the rails. We can only wonder whether disasters were regular.

Later as we chopstick our way through the tasty street food in the heart of Hanoi’s Saturday night buzz, the atmosphere is so good, so enjoyable. Some streets in the old town are closed to traffic tonight and live bands and dance corps do their thing on temporary stages, travellers mix with the bright young things of Hanoi and the whole night feels alive. Even the occasional heavy shower seems to add to the sense of fun. As we head off to bed it dawns on us that we’ve done more than lay our ghosts here, we’ve actually fallen just a little bit in love with Hanoi. It’s a welcoming, entertaining and vibrant city and this time around we are leaving with very fond memories.

But by Monday it’s time to move on, leave the undoubted joys of Hanoi and its record breaking number of mopeds behind, and head for the hills. Two hours on the “limousine bus” later we are settling in to our next home in the small town of Tam Coc, located in the lush green territory of Ninh Binh province, wondering if we’ve somehow brought a piece of England with us….it’s drizzling and it’s chilly.

Actually, the temperature plummeted last night back in Hanoi – the normally T-shirt clad locals suddenly multi-layered, umbrella’d and waterproofed – and at two hours we obviously haven’t moved far enough away to escape the weather trend. We knew to expect this, as we said earlier, but we also knew, or rather hoped, that Tam Coc would look stunningly beautiful in any kind of weather – and we aren’t disappointed, this place is amazing.

Of course, its wonderful scenery is partly down to the fact that it is fantastically lush with at least fifty shades of green, and you don’t get that level of lush without a plentiful supply of water. But it’s not just the greenery: the Ninh Binh Province is another fine example of limestone karst scenery, like having a Halong Bay a hundred miles inland. To say Tam Coc/Ninh Binh is spectacular is an understatement.

Again, the karst limestone giants rise in almost vertical pedestals, creating in the process every form of clever and crazy design you can imagine, and a few more which you wouldn’t. Maybe what completes the surreal look of a karst landscape though is what lies between each peak: nothing. Well, nothing irregular, anyway, the land between the giant towers being perfectly flat and showing no hint of undulation – between these peaks the land is less than four metres above sea level. Consequently the main constant here is water, and not only falling from the sky. Rivers, tributaries and rivulets flow between the rocky highs, lakes form at narrow entrances to caves, and all around are rice fields where the succulent bright green plants stand knee deep in the water which seems to cover every square inch of land between the villages and the karst giants.

Boating along the Ngo Dong River (aka Red River) is fun, not least because your “driver” propels the little craft along the river by operating the oars with his or her feet – it must take a hefty period of practice to perfect the technique, and the learning curve must surely involve an enormous amount of muscle pain. As our lady driver guides us along, storks feed among the rice fields and alight on the cliffs, fish leap from the water at the sight of a fly and goats risk life and limb to feed on the cliff edge.

A few kilometres down the road from Tam Coc lies Trang An, another boating opportunity with an even more spectacular collection of monster karsts but this time without the rice fields. Passing through any of the cave tunnels beneath these monoliths is a surreal experience, some over 300 metres long as they twist and turn through the belly of the limestone. The cave roofs and stalactites drop so low that we have to bend double in the little boat, head between our knees, to avoid stoney contact. These routes would be a challenge to anyone either inflexible or claustrophobic!

When we emerge from the echoey darkness into an area where the waterway is trapped between the hills, the peace and serenity is close to perfection, only bird calls and the plop of the oars to break the silence. On both boat trips our eyes are unavoidably drawn to the scenery, knowing all the time that we are witnessing a landscape which exists in very few places around the world – not quite unique but certainly dramatic and beautiful.

Temples from the Tran dynasty lie hidden in the greenery, most accessible only by boat and footpath, some beautifully housed in caves, others looming in the foliage to look out across the water, all of them guarded by “dragon crane” birds (called Chin Lac) and housing shining golden statues. This dynasty ruled an area roughly equivalent to today’s North Vietnam from 1225 to 1400, garnering a reputation for fierce fighting, high intellect and scientific advancement, playing pioneering roles in both medicine and the development of gunpowder. Today these small temples, filled with the scent of incense, display impressive statuary and colourful artwork: we hike to some, call in by boat to others.

Tam Coc village is definitely on the traveller map and definitely on the backpacker trail, its main street packed with great little family restaurants, its back roads dotted with homestays like ours. Like other similar places which act as a gateway to spectacular sights, it has a certain convivial evening feel to it which is so familiar to the traveller. Its appeal is instant. Even when it rains (Note – actually, during our few days here the rain held off and the mercury started to creep up).

We could happily stay here a few days more, but there’s a whole country to explore….and a sleeper train to catch…

Tam Coc to Hue: Inside The Imperial City

The climb to the dual peaks of Hang Mua is a hefty ascent of over 500 steps which are so irregular and uneven that coming back down is almost as tricky as going up, but the magnificent views from the top make every bit of the effort worthwhile. Sweeping panoramas across the lush green paddy fields, towering karst limestone hulks and twisting rivers lead the eye eventually to the urban sprawl of Ninh Binh city. These views hammer home just how much water there is here: villages are islands and roads are causeways.

At Hang Mua, gardens have been laid at the foot of the hills and a few cafes erected, but its joy is its natural wonder, showing how nature itself creates the best theme parks with minimal human input. Waterfalls cascade down rocks, pools form to support lilies and lotus flowers, fish swim amongst the rice plants, all before we climb those steps and soak in the classic and famous views of the rivers and peaks of Ninh Binh province.

Our last sortie from Tam Coc is to the temple and pagodas of Bich Dong, magnificently hewn into the rock face with small shrines and carvings concealed deep within the winding caves. This complex of three pagodas was constructed somewhere around 1428 and was historically a ceremonial site for Buddhist monks and followers – indeed the site still carries many mantras presented in a rather odd “cause and effect” style. In other words, advice along the lines of “do this, and these will be the consequences”. Reading them leaves us a bit nonplussed, as for every one which is sensible and logical, there is one which is downright ridiculous. Be jealous of the achievements of others and you will end up a hollow individual? Yep, get that. Fail to pray earnestly and you will end up with a physical disability? I don’t think so.

And so we move on. The night train from Ninh Binh to Hue takes a full eleven hours but we sleep surprisingly well in our small couchette shared with two girls from Germany, arriving in the city of Hue just in time for breakfast. Hue is just about the midpoint of Vietnam, being pretty much halfway between Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City in this long narrow country.

Sitting astride the wonderfully named Perfume River, Hue was once Vietnam’s capital, formed in 1601 when the Nguyen Lords turned up here in order to build a city to use as a base to rival their opponents the Trinh Lords. After much squabbling both internally and with others, the 10th Lord eventually founded the Nguyen dynasty in 1802 – a dynasty which would rule the area right up until 1945, although much of it as a puppet Government controlled by the French.

Hue’s Imperial City, a grand affair buried within formidable city walls, was used as a fortress by the Viet Cong during sustained attacks by America in the Vietnam War and Hue suffered extensive damage as a result. Historical monuments and relics were destroyed in large numbers and the Imperial City was hugely impacted: this, coupled with its propensity to suffer typhoons and flooding, leads Vietnamese to refer to Hue as the “sad city”.

Yet as we wander along the neat riverbank gardens, through the busy thoroughfares and around the “night walking streets”, “sad” is not an adjective we would choose to describe this bustling, businesslike city. The Perfume River – so called because orchids shed their fragrant petals into its autumn waters – and its tributaries and canals crisscross Hue and provide numerous locations for boat trips, riverside cafes and the like, not to mention the bridges of various styles.

Entering the Imperial City through the Ngo Mon Gate and across the Golden Water Bridge gives just a hint of the majesty which awaits inside the citadel, another UNESCO World Heritage site. What remains of the ancient city walls is a clue to its level of fortification – these walls are 8 metres high and a crazy 20 metres thick. Since its devastation during American bombing in the Vietnam War, much restoration work has been completed within the citadel – one (tiny) benefit of being destroyed in recent times is that there were plentiful photographic records on which to base the reconstruction. Small compensation but compensation nonetheless.

It’s the vastness of the Imperial City which takes us by surprise, covering an enormous 1,285 acres of city centre land. The mix of original and restored buildings, the extensive gardens, the dramatic and ornate pagodas, all add up to a magnificent site, this was one huge royal family setting. The central section is known as “The Forbidden Purple City” – they seem pretty good with names here!

Having been the seat of Nguyen rule for so long, Hue inevitably saw a whole host of royal deaths, and consequently the city has more than its fair share of tombs and memorials. Even the girl in the mysteriously named “Cafe On The Wheels” tells us not to do too many…”maybe just the best two”, she says. We take her advice, and soon see what she means – these tombs are not exactly modest.

The two we choose are those of Khai Dinh and Tu Duc (stop it, it’s not funny to laugh at foreign names), both huge, rambling complexes which seem to grow in size the more gateways we pass through. The former, in its splendid steepness looking across the verdant hillsides, boasts statues of philosophers and the military alongside those of elephants; the latter is an endlessly rambling series of structures deep in the pine forests where the grating sound of the cicadas is a constant backdrop.

These tombs are not ancient places, dating from the 19th and 20th centuries, but the level of detail throughout these giant complexes is probably the most memorable feature: the ceramic-and-glass artwork at Khai Dinh took eleven years to complete. We can tell them it was worth the effort.

After so many temples, tombs and relics we briefly indulge in a more modern culture: football. When I spot that FC Hue (a second tier club) have a home National Cup tie against top Division opposition it’s just too tempting, so we wander down to the Tu Do Stadium where, much to the disappointment of the locals, class tells and the amusingly named Becamex Binh Duong FC cruise to a 0-4 victory.

Evenings are alive in Hue. As twilight merges into darkness, the neons and the LEDs splash colour into the streets, cafes morph into music joints, roller shutters open to reveal inviting bars, and large numbers of people take to the “walking streets”. One such is clearly the family area as everyone from toddlers to grandparents enjoy the atmosphere; the other closer to a “Pub Street” where the music is loud and the cheap alcohol flows freely.

If this place earned its sobriquet “sad city” in the aftermath of its devastation in the Vietnam War, then it has long since shaken off its sadness with a panache, style and joie-de-vivre which in its evenings is impossible to miss. It feels more like “happy city” to us.

To Hoi An: The Land Of Lanterns

And so we head to Hoi An, a place about which we have heard so many good things that this will be our longest stay in one place whilst in Vietnam, a full six days. Our original intention was to go by train from Hue to Da Nang and then taxi to Hoi An, but we got chatting to a guy in a cafe on the first morning in Hue who told us he can book a bus which will take us door to door for half the price of the taxi alone. Bargain.

Bargain? Well, yes, but boy does the journey bring surprises. Sure enough, we get picked up from our hotel, settle into our bus seats…and then get turfed off about five minutes later and shunted on to a second bus. This one is a so-called “sleeping bus” which, despite the fact that we are travelling through the middle of the day, has no seats, but a series of “beds” which basically means that everyone climbs into a luggage rack, lays down and falls asleep.

Initially the movement of the suspension makes our upper bunks feel like a rolling ferry on rough seas and we fear the worst, but ten minutes in and the rocking sensation becomes soothing and the experience is an unexpected piece of fun. Lisa, our host in Hoi An, sends her brother Ryan to meet us off the bus, but he turns up on a moped and then calls a taxi, despite the fact that about half a dozen taxis were waiting when the bus drew in – and now they’re all gone. All this simply because our hosts insist on paying for our taxi…we appreciate the lovely gesture but there would have been quicker ways!

“Very touristy but very beautiful” is how everyone described Hoi An to us before we got here – a description which is obviously correct from the moment we turn a corner and see what is before us: we’re not sure whether we’re walking into a jewel of a town or into Vietnam’s equivalent of Blackpool illuminations.

There is indeed a certain type of beauty to the thousands of multi coloured lanterns reflecting in the water, and to the lantern-carrying boats drifting stealthily along the river. But touristy too? Oh certainly, both riverbanks are an explosion of coloured lighting, street hawkers and food stalls, and pavements rammed with awestruck wanderers. Restaurant owners call us in, boat owners offer a trip, tat is available at “very cheap price”. Photo opportunities abound.

Both elements – the “beautiful” and the “touristy” have us grinning from ear to ear as we quaff the local beer (Larue), eat delicious food and listen to the live band playing rock classics….Joan Jett, Guns n Roses, Fleetwood Mac…..and Adele. What exalted company the Essex girl’s music keeps these days. Hoi An is beautiful and ridiculous, charming yet OTT. This Vietnam tour is nothing if not varied and Hoi An represents completely new ground.

The colours, the lanterns, the bars, the music, the boats….magical yet crass, amazing yet cheesy. We don’t even know if we like it or not. Yet we love it. It’s so cheesy that the whole town smells of cheddar…no of course it doesn’t, in truth it smells of jasmine, tiger balm and barbecue smoke, but cheesy it certainly is. Massage, Sir? Toys for your grandchildren? Please find your heart and buy, I sell nothing all day today. You want boat? Taxi? Where you from? Oh, England…lovely jubbly.

Not everything centres around the riverfront, Hoi An has a multitude of quaint, car-free streets winding between the age old buildings, nowadays filled with clothes shops and cafes but originally modest dwellings for a cosmopolitan melange of Asian traders. Both the Chinese and Japanese had significant influence here long before the French threw croissants and baguettes into the mix.

Hoi An’s relationship with water is complicated, one of those locations where the boundaries between the widening river, the man made canals and the open sea are blurred, and where it’s hard to work out which is mainland and which is island. Even a lengthy boat trip doesn’t solve the conundrum, it’s a bit like magnifying Murano, dropping it into an estuary and letting Gaudi design the lighting.

Even though Hoi An embraces modern culture with such enthusiasm, this is an ancient town with a long and fascinating history. As an international trading post in the 16th and 17th centuries, foreign merchants flocked here from around the world to attend the major trade fairs, with Japanese, Chinese, Dutch and Indian traders in particular putting down roots. The influence is evident in Hoi An’s ancient buildings: the Japanese Covered Bridge, Chinese and Cantonese Assembly Halls, pagodas and ancient wooden houses.

With the old town now free of cars and open only to pedestrians and the ubiquitous moped army, Hoi An is wonderfully charming – not least because among the large numbers of tourists, fishermen still throw nets across the water and locals still crowd the central market to buy fruit and vegetables unfamiliar to our eyes.

But it’s at night that the characteristic for which Hoi An is most renowned is at its height: the lantern boats crowding the water, the multitude of lanterns strung along the riverside, the colour and verve of its evening persona. Touristy or not, it is definitely a spectacle. The night of a full moon is usually an excuse for a festival anywhere in Asia and particularly where the Buddhist faith plays a role, and more by luck than judgment the Tuesday of our stay is indeed the night of a full moon. Much play is made of the festival, when we are told that all electricity is switched off and the whole romantic scene is illuminated only by candlelight. It isn’t quite true – sure, the street lights and the bridge lights go off, but nothing else does and the reality doesn’t live up to the hype…except for the lantern boat owners who do even more business than usual and pocket a load of extra dong.

Opportunities to do the touristy things abound here in Hoi An: lantern boats, slightly larger tour boats, bicycle tours, cooking classes, electric open trolley vehicles…..and the basket boats. Oh we just have to do a basket boat. These ridiculous little circular craft are, despite the tourist role they play today, a time-honoured feature of Hoi An and its waterways – with an amusing history. As a way of securing income from the area’s plentiful produce, the French imposed taxes on every boat owner, including fishermen and those gathering coconut and other fruit from the watery plantations. The canny locals made the circular baskets and successfully claimed that they were simply waterborne storage vessels and were not used for conveying humans – the French authorities apparently fell for the ruse.

Hoi An is heaven for a clothes shopper and my patience for traipsing in and out of endless stores wears thin before Michaela has even scratched the surface, so I wander off in the heat for a while to explore the more down to earth parts of town. A little lady in a doorway calls out to me.

“Haircut Sir? Very good price”. As it happens, I do need one.

“Where you from?”, she inevitably asks as she cleans off the number 1 blade for the razor. I tell her.

“England, oooohhhhh”, she says, and adds, “you have lovely bald head. I am single”.

“…………”

“Single and fifty five”.

I hear myself blurting out that my lovely wife is shopping in town at the minute. I think I detect just a hint of panic in my own voice….

Hot Days & Warm Hearts: A Week In Hoi An

The advice we’ve been given is that, when it comes to visiting the My Son Sanctuary, we have two choices: go in the morning when the coach parties are doing the rounds and visitor numbers are high, or risk coping with the intense heat of the afternoon when we’ll more or less have the place to ourselves. Seeing as we are one half of the “mad dogs and Englishmen” couplet we opt, of course, for the quieter, hotter alternative.

As it happens, temperatures have raced up the scale since we’ve been in Hoi An and at the same time someone has adjusted the humidity setting so that T-shirts last about twenty minutes before being utterly drenched. It’s bloody hot, in other words. Nevertheless, our decision making vis-a-vis My Son is rewarded with just a handful of visitors wandering around this stirring relic from ancient times. Not a coach party in sight.

As ever in places such as My Son, our thoughts turn as much to the magical moment of discovery by archeologists and explorers as it does to the ancient societies themselves. Think Howard Carter and Tutankhamen, think Burckhardt and Petra. What a moment that must be. Here at My Son the honour falls to French explorer and historian Camille Michel Paris who uncovered My Son after 500 years of it being overgrown by jungle.

The construction of My Son Sanctuary began in the 4th century with evidence of additions and alterations right through to the 14th, after which the site appears to have been abandoned. Set in beautiful verdant mountains and owing its location to the presence of holy springs in the hills above, My Son was a centre of the Cham civilisation, one of the foremost Hindu temple complexes in the whole of South East Asia and pre-dating even Angkor Wat. Some scholars have concluded that, as a site where evidence suggests the presence of up to 70 temples, this may well have been the cultural and religious centre of the entire Champa region.

Camile Michel Paris and his team of French archaeologists rediscovered the site in 1898, with much exploration and restoration work subsequently being undertaken in the 1930s and 1940s, also by the French. My Son was granted UNESCO World Heritage status in 1999. Regrettably, in between those dates the site was extensively bombed by the Americans during the Vietnam War with large sections of the site all but obliterated during a 7-day onslaught. Criminal.

Closer to home and just a hundred yards or so from our apartment is a flamboyantly decorated Chinese temple which has been silent behind its closed doors since we arrived – until today, when the haunting sound of Chinese music and harmonised singing drifts down the corridors of Hoi An. It is, it seems, Tomb Sweeping Day today – a Chinese festival when lost loved ones are remembered, including, as you would expect from the name, tidying up their graves and headstones. More solemn than the party in Mexico which is the “Day Of The Dead” but a similar principle. Hmmmm…the Chinese more solemn and less party spirited than Mexicans…..who knew, huh!?

In amongst the cobbled streets in town, tucked in amongst the many gorgeous old buildings, is the House of Tan Ky, a timber built dwelling which has been in the same family for generations – so long in fact that the original owner amassed his wealth in the heady days of the late 18th century when Hoi An was a major port and trading post. Now, the house is partially open to the public, granting its visitors a peek at how life has been lived across seven generations, together with a little piece of Hoi An history.

The place is a veritable museum, a rolling review of history, and yet is still home to descendants of the Tan Ky family. On one wall there is a series of markers demonstrating the height of various disastrous floods over the years, showing eleven different floods across the last 60-odd years. The highest is only just below ceiling level – the family has had to rebuild and/or renovate on each occasion.

Back to our own apartment, where inanimate objects have started to move around on their own. We’re just dozing off when there’s a noise from the kitchen area – when I venture down to look, the box of Lipton tea bags which was on the worktop is now in the middle of the floor. Earlier, the tube of Lay’s crisps had been knocked on to its side, the plastic lid displaying strange piercings where there shouldn’t be any. Crockery clinks when there’s no one downstairs. It’s not a poltergeist though, we already know from the mouse droppings who our uninvited visitor is.

Ryan – our host’s brother – is in a hilarious state of apoplexy over the matter, unable to explain how a mouse has joined the party and failing to realise that we are amused rather than distressed. Ryan’s mother, brought along by him to do Mum-type things, has no English but quickly reads the body language and is just as amused by her son’s misplaced consternation as she is by our casual stance. Calm down, Ryan, it’s fine – we’d take a mouse over a cockroach any day of the week.

Hoi An’s riverside often has a cooling breeze coming in from the sea, a very welcome respite from the extreme heat of the day which hits us every time we move away from the waterfront. It’s the kind of heat which makes metal railings and door handles untouchable and the barefoot approach to a temple feel like a dash across hot coals. So after a few days of exploration and adventure around the area, it’s so nice to grab a few hours at An Bang beach where the sea breeze is stronger and the South China Sea cools our ever boiling blood. There’s some fantastic fresh seafood to be had at the beachside restaurants too.

During the last week we have seriously come to love Hoi An. When we arrived here and saw the touristy bit for the first time, we wondered if six days would be too long to be here, yet now we find ourselves not only knowing we could happily stay longer but also adding Hoi An to our shortlist of places around the world where we could settle down and live for several months. If we ever do that, then Hoi An will be near the top of that list.

It pretty much has everything. Ancient sites, a beautiful old heritage centre, the waterfront which brims with activity and, away from the heritage and the tourism, a gentle, ordinary town meandering its way through life. With so much to offer in the town itself, and so much beauty in its hinterlands, it’s just a bonus that Hoi An is a place where you can…..

Head to the beach…..

Spend an evening in a riverside bar……

Watch the lantern boats……..

Eat a frog on a stick…….. and go home on a moped…….

Da Nang: The Modern Face Of Vietnam

Laying our Vietnam ghosts has been such an edifying process, we now have a very strong affection for this country after our bad times here at the onset of COVID when we met with some real hostility simply because we were British (this was when the pandemic had taken a stranglehold in the UK more than anywhere else). We’d also had bad food experience, the meals we ate in Hanoi back then were consistently poor, a bit like being given a bowl of washing-up water where if we were really lucky the dishcloth had been left in the bottom.

We always knew though that this was not typical – every single traveller we’ve ever read or listened to puts Vietnamese food near the top of their World food list. It’s massively pleasing to now be able to share that opinion, the food this time has been nothing short of fantastic. Some of the flavour combinations here are beyond inspired, with constant surprises to delight the tastebuds and not a single meal ever feeling stodgy.

There’s often a hint of sweetness lurking beneath the herbal tastes of a savoury dish; a surprise prawn (shrimp) will give a twist to a bowl of pork noodles; coconut coatings enhance seafood; fresh mint leaves make marinated goat burst with flavour; dishes which at first look ordinary turn out to have different flavour notes in every mouthful. The whole cuisine is a constant joy and a constant journey.

Honestly, we could go on….but pictures speak louder than words….

And then there’s the coffee. Or rather, coffees…..egg coffee, coconut coffee…and “Vietnamese coffee”. Order a Vietnamese coffee and you’ll most likely get a cup of strong black stuff, a small jug of gloopy sugar cane syrup and another small jug containing condensed milk. You add the two extras to suit your own taste, meaning you can go anywhere from sugar free to something which is so sweet that it probably constitutes a full day’s calorie intake.

After three weeks here it’s now almost impossible to recall that we met with hostility three years ago: Vietnamese people just ooze friendliness, courtesy and calmness. Smiling eye contact is the norm: this is a caring, humble and respectful race so charmingly approachable that they are entirely capable of restoring one’s faith in humanity as a whole. Absolutely lovely people.

The mouse in our apartment has been christened Gerald, Pink Floyd or Syd Barrett fans might get the connection. For a while we only see clues to his existence and catch no sight of the creature himself, until somewhere around Day 4 when Michaela spies him skidaddling across the tiled floor like some miniature bambi. He slaloms to the corner of the room…and vanishes. The only explanation is that Gerald – or maybe there’s a family of Geralds – is living INSIDE the sofa: we can see a small entry hole which must be the front door to Chez Gerald.

News of Gerald’s possible living arrangements does not go down well with Ryan when he comes round to say goodbye and collect our keys and for our last fifteen minutes here we have a headless chicken in the apartment as well as a mouse. We leave Ryan to solve his intruder issues – and we leave Hoi An too, with extremely fond memories of a very welcoming stay. We love you Hoi An.

By our standards it’s a short hop to our next destination, just a forty minute drive up the coast to Da Nang, but it’s yet another huge leap in culture and may as well be a million miles away from the likes of Tam Coc and Hoi An. Da Nang is the contemporary face of Vietnam. With a history of wealth generated by its role as the country’s major port, someone realised somewhere around twenty years ago that a bright, prosperous city with an unbroken 6 mile stretch of golden sand might just be able to attract visitors. They were obviously right.

The result is a curving bay which looks something like a scaled down Rio or Acapulco, dozens of high rise buildings following the line of the seafront pretty much as far as the eye can see in both directions. Huge open plan restaurants straddle two floors, letters reading “HOTEL” and ”CASINO” appear regularly along the strip, street vendors peddle their wares and crowds flock to the beach as the afternoon sun tempers its heat and drops below the skyscrapers. The exciting variety of our stops on this trip continues: Da Nang bears no resemblance to anywhere else we’ve seen in Vietnam.

The marketing of Da Nang has, we learn, led to the city becoming a favourite holiday destination for people from South Korea, and in high season the local airport handles nearly 250 flights a week from the three main Korean cities. Work on the development of Da Nang the resort is clearly far from finished, too – more and more skyscrapers are half built skeletons and there are more construction sites than you can shake a stick at. We try to count the storeys on one of the new ones but somewhere around floor 50 we go cross-eyed and lose count. This sure is the modern face of Vietnam.

We know it’s very British to harp on about the weather but there’s an intriguing phenomenon here. Mornings are still and sultry, the sun hazily obscured by clouds, too hidden to be properly visible yet strong enough to cast shadows. Somewhere around 2pm the sea breeze starts to blow away the humidity and turns the docile sea into a succession of crashing waves perfect for body surfing and other daft fun.

But it’s the clouds which really fascinate. As the breeze increases, so the clouds move across the bay, gathering along the line of mountain tops in ever increasing whiteness like giant rolls of cotton wool. The rest of the bay now basks under clear blue sky. As dusk approaches, the cloud creeps over and down the mountainside, becoming not so much cotton wool as icing on the Christmas cake. It is mesmerisingly beautiful.

After dark, Da Nang buzzes as the cafes fill up, neons burst into colour and skyscrapers become gigantic displays, sometimes advertisements, sometimes the national flag. We simply keep staring at this improbable, impressively modern vista. The nighttime cityscape is positively futuristic, a completely new perspective on Vietnam, a spectacular and dazzling skyline which speaks of a bold, progressive city. Even Hanoi the capital didn’t look like this, and it’s hard to believe the rice fields of Ninh Binh are even in the same country.

Someone tells us that Da Nang is taking its inspiration from Singapore. We can well believe it.

The Bridges Of Da Nang And A French Village In The Sky

Da Nang is a large and sprawling city, and our time here is very short – plus, we’ve discovered that the sights which we want to visit are a distance apart from each other and are all some way away from our seafront hotel. Sipping draught Tiger beer on our first night here, we are just debating whether hiring a driver for a day might be our best solution, when we look up and see a guy with a plastic wallet full of leaflets making a beeline for us across the road.

“Hello”, he says, “my name is Mister Tony. You want find a driver and guide for your stay in Da Nang?”

Either he’s a mindreader or Tiger beer has some remarkable qualities. So only half way down our second pint of Da Nang’s best we have agreed an itinerary, negotiated a fee, swapped WhatsApp details and put everything in place. Funny how these things work out sometimes.

It’s lucky we’re here at a weekend as we get to see a feature of Da Nang which is a little bit special. Several bridges span the wide Han River which cuts a swathe through the centre of the city, one of which, the Cau Rong (Dragon Bridge) has become something of a national treasure since its construction ten years ago. I mean, if you have to build a big bridge over a city centre river, why not build a giant dragon feature which runs across its entire span, head at one end and tail at the other?

At night, the Dragon Bridge lights up with ever changing colours, but it’s just before 9pm on Saturdays and Sundays that hordes of people flock here to see the spectacle which causes all the furore, because it’s at that time that the dragon breathes fire across the street. Really. It’s quite a sight and one which excites children and grown up children in equal measure, as the dragon’s head spouts long bursts of flame, followed by several powerful jets of water, into the air above the street, the whole show lasting around twenty minutes. The appreciative crowd cheer and whoop at every piece of action.

Around the vicinity, this iconic bridge has spurned numerous beer houses, street food stalls and a thriving night market, all catering for those who come to see the bridge, the event, or both. It’s an atmosphere all of its own.

One of the admirable characteristics of the Vietnamese is their attention to detail, they simply don’t leave loose ends. When you make an arrangement, they will contact you several times to check everything is still in place, and consequently there is never the slightest doubt that things will go according to plan. It’s a compelling virtue which is one hundred per cent reassuring.

It’s exemplified by Mister Tony, who messages several times on Sunday then arrives on the dot at 9am Monday morning to take us around our chosen sites, first to the Marble Mountains back a couple of miles along the coast road towards Hoi An. This is another intriguing site with temples and shrines hidden within the recesses and caves of these strange looking rocks. Before being made illegal, unofficial miners were extracting the marble in order to fashion statuettes for the souvenir shops: a process thankfully now halted, meaning these centuries old shrines have survived both pillage and war over the last sixty years alone.

After the mountains we head to the hills – the Ba Na Hills to be precise, where the concept of Da Nang being the modern face of Vietnam is taken to a whole new level, in more ways than one. At the foot of the hills is an entrance so grand that we could just as easily be entering a 6-star resort in Miami; next come courtyards and gardens re-creating the feel of old time Hoi An – then, as if the senses aren’t already reeling, we board what is claimed to be the longest cable car ride in the world.

This run brings us to the sight we have specifically come to see – the Golden Bridge. We are now more than 1400 metres above sea level, yet here is probably the most eye catching footbridge we’ve ever seen, an incredible feat of imagination. It takes an inspired mind to dream up a bridge held up by massive hands cupped around the platform and stick it way up a mountain. Well, an inspired mind and considerable financial resource.

In fact, whilst the colossal hands which appear to be holding up the bridge look as if they are hewn from the adjacent rock face, they are actually fiendishly designed from fibreglass and wire mesh – they are not stone at all and they don’t actually support the bridge structure either. Nevertheless it’s a fabulous sight and an engineering marvel, not least because it serves no real purpose other than as a tourist attraction. It’s certainly worked, it’s already an unmissable feature for anyone visiting these parts. If this amazing bridge, completed only five years ago and which curves crescent shaped on the mountainside, appears to be ostentatious, then what comes next puts it into perspective.

Further up via a second, shorter cable car journey, is the Sunworld Ba Na Hills Resort, not yet quite complete and with much construction work still in progress. What a weird, though hugely popular, place it is. Part amusement park with “alpine” rides and the like, the main area is an entire mock French village complete with a Mercure Hotel, a town hall and numerous restaurants, sitting here almost 1500 metres above sea level in central Vietnam. The cable car stations are named Marseille and Bordeaux.

Neither of us have been to a Disney location and neither of us has a desire to do so, but Sunworld Ba Na must be something like one. Apart from a spectacular dance show in the main square, this is not our cup of tea…nor is the fact that a cup of tea, like everything else up here, will cost you about five times what you’d expect to pay in downtown Da Nang. The thing is, though, it’s worth every centime to take the lengthy cable car ride and especially to see, photograph and walk along that iconic bridge. It’ll probably hit some “wonders of the modern world” lists before long.

Mister Tony is waiting for us back down in the car park.

“You hungry?” he asks politely. We’re ravenous as it happens. “OK, I take you to special place, best Vietnamese food”.

Now that sounds good, based on the evidence of the three weeks of food from the Gods which we’ve already enjoyed. He pulls the car into a ramshackle market place back in Da Nang, and walks us through to a food stall with plastic seating (of course) where smells from heaven waft through the air.

“What Vietnamese food you like?”

“All of it”.

“OK. What foods you not eat?”

“Nothing. We eat everything”. He, and the lady cook, are visibly delighted at our answers.

And we are just as delighted with what we get served, one of those uplifting, brilliant occasions where we have no clue what we’re eating and every mouthful is another taste of ambrosia. The fantastic food experience of this whole Vietnam trip has just got even more exciting.

Thank you so much Mister Tony, you’re a good man.

Down To The Delta: Markets On The Mekong

We seem to get from Da Nang to Can Tho in the blink of an eye, via a domestic flight which leaves on time and arrives early followed by a taxi driver with Formula 1 aspirations. Our base in Can Tho is in the Ninh Kieu district, close to the quay of the same name, and as we take our first stroll and look out across the water, there is a serenity which we think is like a Spanish siesta, but will come to realise later that it is something else entirely.

The mighty Mekong River travels some 3,050 miles from its source high on the Tibetan Plateau down to the Delta, passing through six countries as it makes its complicated journey south. With a history of trading and trade routes going back thousands of years, the Mekong has for centuries, and continues to, sustain the livelihoods of millions of people along its route.

Throughout its course the Mekong is not only joined by many tributaries but also spawns distributaries multiple times, particularly as it nears the delta region close to Can Tho. From here, five separate major waterways spread out into the delta, known by the locals as the “five dragons”, one of which, the Hau, branches off through the centre of the city whilst the Mekong proper passes beneath the imposing Can Tho suspension bridge still within the city limits.

Life here is all about the water. The floating markets for which the area is renowned, bustling fish markets, fleets of traditional sanpan fishing boats, plots of water borne vegetable crops, all manner of commercial river tour operators…..and even garishly lit night cruisers featuring bars, restaurants and karaoke. The community lives off the proceeds of the Mekong, one way and another. It also has to cope with its moods: the Mekong bursts its banks regularly in rainy season and floods many of the homes-on-stilts which face on to the waterfront.

Outside of the rainy season, a huge expanse of water such as this moves at a leisurely pace, bringing a deceptive calm to the air which at times makes even the chugging of a tour boat sound restful. It is indeed deceptive though: Can Tho is not really a restful place, and we can only imagine how different this city must look when the siege of flooding is under way.

Our apartment in Can Tho sits above the Vado Canteen, a cafe with a regular flow of customers which never quite equals the number of staff. Each time we arrive back at the place, the old guy who we assume to be the owner greets us with a smile and a chirpy “xin chao” as he sports his orange T-shirt to match his staff’s uniform. Those staff, all of them diminutive figures, open the door for us, form a guard of honour and smile sweetly as we pass through – it’s not really a guard of honour, it’s just that the cafe is so small and cramped that they have to stand aside to let us through. We then pass through the kitchen which smells of something similar to boiled cabbage, and where there is always one staff member fast asleep amongst the boxes, then on up the stairs to our apartment which is, thankfully, a roomy and airy space. At no stage do we get tempted to eat downstairs.

It’s an early start for us on the Wednesday. Our host tells us to be outside the cafe beneath our apartment at 5:30am; we go down a little early and our guide Lin is already waiting. We’re soon off on our chugging craft on the water, heading towards the renowned Cai Rang floating market, the sun trying and failing to break through the heavy morning sky. Along the riverbank, three-sided stilted houses are open to the elements and creaking old house boats sport lines of washing; people wash their bodies in the murky waters whilst up on deck kettles steam on miniature stoves and men wallow sleepily in their hammocks.

The handsome Sheraton and other hotels tower over the river and not for the first time on our travels we are struck by the extreme gulfs in wealth in a local environment. These are such humble dwellings. These are such swish hotels. They stare at each other across the water, separated by a river yet existing in different worlds.

Cai Rang itself is an age old floating market, a wholesale market in which the traders live on the river, their houseboat and storage boat tied together. Their life is one of sailing upstream to the farmers, buying produce, returning to the city and selling that produce to shopkeepers and night market stall holders in town. Buying from the supply boats which cater for the market, we eat a bowl of pho (for breakfast, too heavy this early!), drink amazing coffee and scoff fresh juicy pineapple.

Around us cash is changing hands, stashes of pineapples move from boat to boat, traders do deals over piles of pumpkin; but there are just as many boats idling in the water, traders sat on their haunches waiting for something to happen. For every flash of life there are ten scenes of nothingness.

And so in truth Cai Rang is a bit of a disappointment, not quite the vibrant, colourful hive of activity we had read about, more a collection of tired old boats laden with a single type of fruit, the air full of petrol fumes and the water writhing in floating plastic. Lin tells us that Cai Rang is nowhere near as manic as it once was, and seems to be shrinking annually, a shadow of its former self.

“There are easier ways to make money” she muses, “especially for the young”.

One of those ways is probably the more conventional street markets in town, or maybe serving in restaurants, or more likely still, heading off to the bigger cities. The renowned Trang Phu street food market, our other intended destination here, has shut down completely: always on our list of exciting experiences in this town, to our disappointment it simply no longer exists. The quay at Ninh Kieu is seemingly the new heartbeat of Can Tho, the garish karaoke boats competing for customers as the music gets louder, boat tour vendors pestering people to commit to a 5:30am start for the Cai Rang tour, electric buses ferrying revellers to and from the waterside. But supply outweighs demand by some distance, both on the quayside where the hawkers soon sit down and give up, and in the empty eateries where owners sit waiting to fill just one table.

It’s notoriously humid here. The heat is stifling throughout our stay, yet the sun rarely makes an appearance, trapped the other side of a colourless unforgiving sky which squeezes the humidity down to ground level. No wonder this city takes a siesta – a casual stroll is totally sapping. Only the rats are active all day, and with plentiful supplies of water, food and garbage, Can Tho easily wins our all time “rat viewings per hour” award. They are everywhere. In every street, under every bush, in any kind of doorway. Even on the butchers’ slabs.

Can Tho is an odd one. Las Vegas style lighting screams out from bars full of empty tables and idle staff; the live music of Hoi An and Da Nang is conspicuous by its absence; drivers of electric buses lazily wait to be approached rather than tout for business. Street food stalls are over stocked and have no queues, their selection wilting in the heat, yet the strip of mostly empty bars looks at first glance like London’s West End, bright neons shining up into the night sky.

The Lotus Bridge flashes its multi coloured LED, the karaoke boats sparkle like fairground attractions, and one major street – Dai Lo Hoa Binh – would challenge Oxford Street at Christmas in terms of overhead lighting displays. Yet go to a Sky Bar and you will find eight staff looking after six customers; look down on the flashing displays of the Lotus Bridge and there will not be one person crossing, or taking photographs. Track down the restaurants serving genuine Vietnamese dishes, as we do, and you will have the place to yourselves.

We wonder whether Can Tho can make its mind up about what it wants to be: its attempts to be a hotspot are incongruous and half hearted, its claims to fame (the marketsn) are dying a slow death, it dresses like a clubber but acts like a librarian. Can Pho is a jigsaw puzzle where the pieces don’t match, a youngest child lacking the charisma of its older siblings.

Overall, our recommendation is…if you want to see the floating markets, do it on an excursion from somewhere else, because Can Tho really doesn’t have a great deal to offer.

On To Saigon Or Whatever It’s Called

Day 35 of this trip and we cop out for the first time. Up until tonight it’s been local food all the way….Indian, Nepalese and Vietnamese dishes, local specialities, street food, even a frog on a stick for God’s sake. But Can Tho is different: the restaurants aren’t quite as inviting, the atmosphere is less accessible, and the street food we’ve tried is unpopular with locals and close to inedible. So we cop out and find an “ordinary” restaurant, The Lighthouse, which, perish the thought, does steaks and stuff.

For the first time since we entered the country, we eat some non-Vietnamese food: Michaela’s is a French dish, mine Belgian. In truth, the food is nothing special, but how good is it to knock back a decent bottle of Malbec: it’s like putting our own blood back in our starved veins.

Can Tho, as we said in our last post, doesn’t have much to offer, and filling our last day here is piecemeal, despite enjoying the best sunshine since our arrival. We embrace a couple of interesting temples, and the Kham Lon Prison which, like the Hanoi Hilton, has a history of brutal treatment of political dissidents by the French during the colonial era. It’s presented in a gratuitously blatant style, mannequins of suffering prisoners displaying despair, dismay and evidence of physical abuse: black eyes, bruised faces, bleeding wounds…. and pleading faces. It unreservedly hammers home its message.

One of the regular architectural features of this journey through Vietnam has been the oddly narrow yet tall buildings, often five or six storeys high but only one room wide. They appear strange, like oversized Lego towers. Asking about this, we find that the very logical explanation is that land is expensive, but building materials are not – hence it’s much cheaper to build upwards rather than outwards. Cheaper to build out over the water, too.

And so we head to our final destination in Vietnam, the city with two names – Ho Chi Minh City aka Saigon. The new name was forced upon the reluctant Saigonese upon unification in 1976, but despite the old name being officially dropped, and in some cases barred, the change has not been implemented universally. Every time we have heard the city mentioned, it’s been referred to as Saigon; the airport code is SGN, the railway station is “Saigon”, the city sits on the Saigon River, the newspaper is the Saigon Times and even the official tourist agency is Saigon Tourist. And with apologies to Uncle Ho and his followers, you have to admit that “Saigon” has far more romance attached to it than “Ho Chi Minh City”.

Sleeping buses are brilliant. This time we’re in the more comfortable side beds, and once we’re in our respective capsules, we have room, comfort and private space as we watch the world pass by the window. If you’re thinking of travelling Vietnam, don’t ignore these sleeping buses, they are their own kind of luxury, and incredibly good value for money – about £6 each for a relaxing 4-hour journey.

While Michaela gets to work on the blog and on Saigon research, I just whack on the headphones and lose myself in a world of shuffle as Vietnam rolls by. Paul Weller barks 80s angst at the rice fields, a Child Of The Universe joins me as we cross the wide rivers, ZZ Top want someone to give them all their lovin’, Dusty Springfield laments that her lover has no heart. Just as Roseanne Cash tells me that our love has become a runaway train, I sense the AC go off, which usually signals an imminent comfort break. We pull over.

There’s an announcement by the driver In indecipherable Vietnamese, and chatter amongst our fellow passengers. What needs no translation at all is the sight of our driver carrying three things past my window – an oily rag, a spanner and a deep frown. There’s clearly an issue. After a bit of twiddling he manfully limps his big bus to the next service station where a team of grimy but smiling mechanics are waiting, eager to help us on our way. In the end we’re only delayed by about 45 minutes before we’re back on the highway heading for …. errr….Ho Chi Minh City according to the road signs, Saigon according to our tickets.

Once we’re inside this instantly appealing city, the biggest city in Vietnam despite not being the capital, it’s “Saigon” everywhere, the only mention of HCMC is on the uniforms of policemen and municipal workers. Our journey through Vietnam has thrown up an amazing variety of destinations but with one unchanging constant: mopeds. Until you come to Vietnam you just cannot imagine the two-wheeled armada which greets you at every road crossing – it’s absolutely unbelievable. In fact, someone earlier on this trip told us that there are five motor bikes for every household in the entire country, something we can easily believe.

Central to Saigon’s pride is the Independence Palace, once the seat of French colonial Government, then the home base of the South Vietnam ruling family before their overthrow and murder. The original palace was destroyed by American bombing and rebuilt in the 1960s, and somehow the architects have managed to encapsulate everything bad about 60s design: the outside looks like a huge Holiday Inn, the interior more like a polytechnic or private hospital. It’s a charmlessly clinical place, ill befitting of the name “palace”.

Saigon is a city with an intensely troubled history, ravaged by Civil War, divided by politics and flattened by bombs, yet its contemporary version of itself is utterly joyous. This is a bold, cosmopolitan, internationally flavoured city with a modern look and a bustling, fast moving personality. It feels uplifting from the very first moment we jink and swerve our way through the moped armada.

The ancient and historic central market, Ben Thanh, still bustles and buzzes with activity, the streets throb with life day and night, green spaces fill with people. Grand buildings from the French colonial era strut with pride, sweeping boulevards form causeways between the back street districts, huge swanky skyscrapers look down on the busy streets, gleaming modern shopping malls are home to the best designer shops. Saigon is every inch the modern, vibrant metropolis where every moment carries the vibe of a capital city, even if it isn’t one. It’s brilliant, in short.

Cultures and histories mix deliciously. Coffee bars serve baguettes and croissants; bahn mi stalls are at every corner; for every designer store there are dozens of street peddlers. Bowls of pho and bun bo are scoffed on every pavement, yet pizza and pasta houses are busy, locals fill the Starbucks near the market. It’s definitely Vietnam, it’s definitely Asia…but this is a modern international city bursting with worldly wisdom and self belief. That alone makes Saigon wonderful, given its 20th century traumas.

Saigon certainly has its party side too: Bui Vien is Saigon’s answer to Bangkok’s Khao San Road, a relentless, electrifying club street where the party is already well underway by 8pm. We throw ourselves in, hoping not to feel too old… and then get trapped there when torrential rain sets in as the evening unfolds. To our delight, even here amongst the revelry, the hedonism and the podium dancers, amongst the tiny mini skirts and the hip swivelling male dancers, amongst the pounding beats and the relentless street vendors…..the food is fantastic.

And so for the next couple of hours we have no option but to drink copious amounts of beer, eat fabulous food and watch dancers and fire eaters.

Travelling can be so tough sometimes.

We Have To Mention The War

“Everybody has heard of the Vietnam War, right?” asks Mickie the tour guide as the minibus heads towards the tunnels.

“Well”, he continues, “let me tell you there is no such thing. My country has a history of a thousand years of war. After World War 2 we have the Indochina War, the French War, and then, the one you call the Vietnam War”, he pauses for effect, “we call the American War, not the Vietnam War. I hope before you leave Vietnam, you will understand more about the American War”.

Mickie is impassioned, proud of his country, and – like every single Vietnamese – from a family devastated by wartime killings. We do, as he hoped, learn more about the American war.

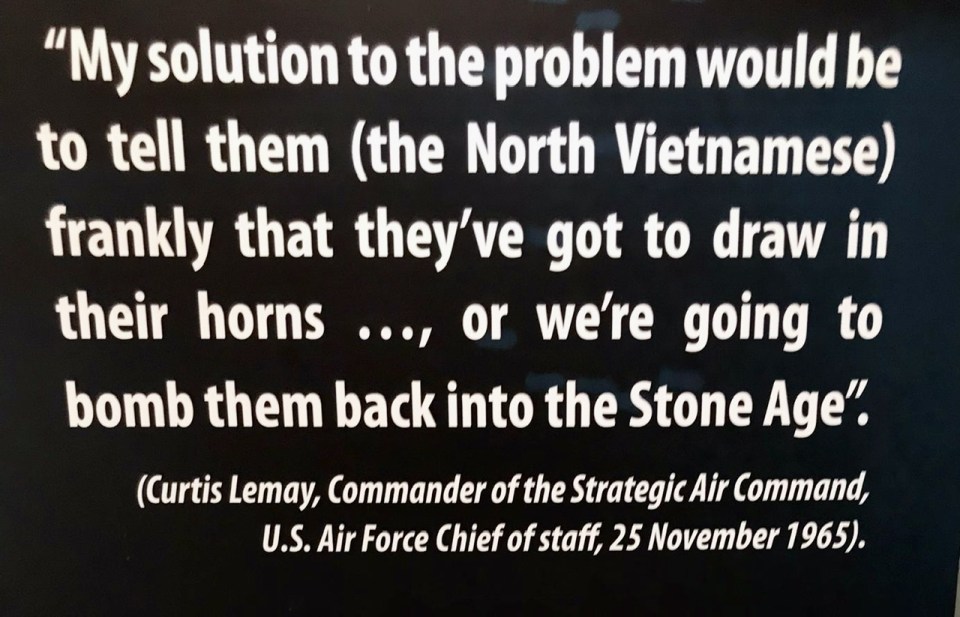

In the centre of Saigon is the War Remnants Museum, and, speaking as people who have visited Auschwitz, KGB prisons and the like, this is one of the most disturbing, harrowing, tear-jerking places we have ever visited. We’re not even sure we can write about it any detail. Our eyes sting with tears as we read of children who were mercilessly slain as harmless villages were wiped out, our brains recoil as we read of the methods of torture inflicted on ordinary civilians, of the inhumane brutality, of the wanton destruction of lives and livelihoods. Maybe just read this…

This is the closest any museum has ever come to bringing me to my knees. I briefly contemplate kneeling down and hiding my face before I manage to gather myself and carry on. How can human beings do these things to other human beings. And this is America. In my lifetime, in my memory.

Michaela and I look at each other, and she looks as drained as I feel. Then upstairs on the next floor, a section on Agent Orange, the appalling dioxin which the US dropped across vast areas of Vietnam. Its deplorable objective was defoliation: strip all plants of life and the population will starve. That’s exactly what it did: everything died. Crops, trees, fruit trees, palms, all became lifeless stumps. If that objective alone is horrifying, then the other effects of Agent Orange are heartbreaking: horrifically damaged bodies, but with the lasting punishment of genetic mutation. Children of those who inhaled Agent Orange were born with horrific deformities, and it didn’t stop there – their children, the grandchildren of those infected, were also born with similar mutations. Chemical warfare with horrifying consequences for three generations of innocent people. If that’s not a war crime then we don’t know what is.

Even now, some 2,000 FOURTH generation babies have similarly borne the scars, and babies are still being born with the impossible, heartbreaking consequences of this terrible, terrible campaign.

I don’t even know what to say as we walk away from the museum. We walk silently across the park. I don’t think we will ever forget what we’ve just read, and what we’ve just seen. Mickie had told us that if we have a heart, we will cry while we learn about the “American War”. It doesn’t need to be too big a heart, so harrowing is the detail. And, yes, we cry.

Our excursion under Mickie’s guidance is more light hearted than the museum though, if indeed this is a subject one can ever be light hearted about. The tunnels in question are the Cu Chi Tunnels, roughly 90 minutes on the minibus out of Saigon and right out into what were the brutal battlefields of the “American” war. This is the site where the under-equipped and outnumbered Viet Cong fighters held out against major onslaughts from the US – outnumbered but not outwitted, fighting on terrain which they understood so much better than their opponents.

An entire network of thousands of miles of underground tunnels and bunkers enabled the guerillas to not only conceal themselves from the enemy, but also to spring surprise attacks. Life went on in these underground chambers as the aerial bombardment, no matter how sustained, failed to defeat those living below ground. As well as the tunnels, tiny hiding places from where the agile Viet Cong were able to pop up, shoot to kill, and then vanish. Michaela disappeared into one such hiding place….

We crawl through a long stretch of tiny, cramped tunnel – only when we are congratulated by Mickie at the far end does he tell us that very few visitors make it through the entire length without opting for one of the escape routes for one reason or another. We can well understand that – to do it you need to be bodily flexible, not suffer claustrophobia and not be freaked out by darkness. It seems a long time before we reach daylight, but we feel good that we both made it through.

For an extra fee we get the opportunity to fire AK47 rifles, missing the target on every occasion but enjoying the experience nonetheless, before being shown in graphic detail the booby traps which the Viet Cong created to intercept advancing GI’s. The traps are pretty gruesome, and almost always fatal, designed to inflict yet more damage to the body if the victim tries to wriggle free.

To resist a better equipped army with greater manpower, the Viet Cong needed to be ingenious, and ingenious they certainly were. As well as the tunnels and hidey holes, the metal spikes inside the booby traps were fashioned from American bombs and tanks, gunpowder from unexploded bombs was recycled and used against the enemy, GI uniforms buried in the undergrowth to confuse the sniffer dogs seeking those hiding in the tunnels.

Cu Chi was a battleground in every sense, crucial to Viet Cong survival and pivotal to the outcome of this senseless war. “We fought hard”, explains Mickie, “because we knew that if we lost Cu Chi, we lost our country”.

Back at the War Remnants Museum, one section focuses on the last days of the conflict, as the US and Vietnam sought a final agreement in Paris. With talks heading towards a solution considered less than perfect by the Americans, negotiations collapsed and, in a final show of brute force intended to strengthen America’s position at the table, Richard Nixon ordered the biggest bombardment of the entire conflict, dropping over 100,000 tons of bombs on target cities in a 12-day offensive known as Operation Linebacker II.

Startling Vietnamese resilience repelled the attack, a victory which was nicknamed “Dien Bien Phu in the air”, citing the name of a victory over the French 20 years earlier. During this final battle, 34 American B-52 bombers, thought to be virtually impregnable, were brought down by fighters on the ground. The terrible war was finally over. We all know the outcome.

In Cu Chi, only 4,000 of the 16,000 underground dwellers came out alive at the end of the conflict, the greater number having been killed by malaria rather than enemy fire.

Mickie has been upbeat, forthright, he’s been passionate and informative. He’s spoken of atrocities without bitterness, of his country with enormous pride.

He bids farewell by telling us to enjoy and make the most of Saigon. “We have seen enough horror and now we have the greatest city in the world. I hope you leave here with good memories”.

4 Comments

Ankit traveler

This blog on Vietnam tourism is fantastic! I appreciated how it highlighted the diversity of experiences available, from trekking in the mountains to soaking up the sun on the best beaches in Vietnam. It’s definitely convinced me to add Vietnam to my travel bucket list. Thanks for the insightful recommendations!

Phil & Michaela

Thank you for your kind comments

VM Car