Greece 2024

Tavuk Sis To Souvlaki: From Turkey To A Greek Island

What in God’s name possessed us to decide to leave the waterproofs at home? How on Earth did seasoned travellers like us make the conscious decision to leave them out of the backpacks until next time? Well somehow that’s what we did, which is how we come to be heading to the ferry in the early morning light by lurching from shop doorway to shop doorway in order to keep out of the worst of the rain. Mercifully it eases off just as we reach the open territory of the dock and we can pick our way through the puddles without getting a dousing. Just.

An hour later – though actually at the same time due to the disparity between Greek time and Turkish time – we are picking our way through puddles which speak a different language and reflect a different world. Our ferry takes an hour but the more expensive catamaran can do the same crossing in just 20 minutes – it’s really strange to think that there’s only such a short time between these two places yet the difference in culture and heritage is so plain. Five minutes of walking from passport control to the town and this is indisputably, unmissably Greek.

We have arrived on the island of Kos and it’s just after 9am on a November Monday. Much of Kos Town is closed, more so even than Fethiye or Bodrum – the doors of big restaurants are padlocked and the chairs are on tables indoors, tills and card machines switched off for the winter. A-boards are stacked behind windows, menus removed from the now empty lecterns, chequered tablecloths resigned to hibernation and there are even ATMs which are sealed off and out of bounds till next April. The season is well and truly over, the locals have their town back for a few months. It’s chilly, it’s cloudy, mopeds splash through puddles – Greeks are not renowned for early starts at any time of year but on a grey November morning it’s as if nobody is smelling the coffee yet, let alone climbing out of bed.

“What are you doing here?”, asks the lady in the grocery store, and frowns when we tell her our reasons. “But it’s cold now, why come now?”. As we are very soon to discover, there are real bonuses to be had by coming here now, not least the fact that those establishments which are still open are the genuine tavernas, those where the locals come out to eat and the village wine takes the value-for-money factor to a whole new level. Another 5 euro carafe with your souvlaki, Sir? Oh, go on then.

Kos Town has a legitimate claim to be the birthplace of medical care as we know it. Beneath the plane tree in the centre of town, the legendary Hippocrates, born on the island, taught lessons in medicine to eager pupils. A descendant of the plane tree, now an ancient being in its own right, stands supported by scaffolding in Kos Town centre. A few miles inland from the town lies the Aesklepion, an extensive ruin on four terraced levels, believed by some historians to be the World’s very first site of medical education and treatment. Mind you, some of those early treatments were a little, erm, interesting. Playing tricks on people doped with opium smoke to make them believe they’d had a visitation from God, and locking patients for a night in a pitch dark chamber filled with snakes were just two of the treatments designed to “shock the sufferer into good health”. You can’t get those on the NHS.

Kos the island has to say the least a varied history in terms of occupation and ownership, passing through Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Genoese, Ottoman and Italian eras, in that order, until occupied by the Germans during WWII, briefly becoming a British protectorate upon cessation of the war and finally ceded to Greece in 1947. Despite this changing history and the relatively short time it’s been held by Athens, Kos absolutely feels Greek.

Mornings are heralded now by the chiming of bells rather than the call of the muezzin, it’s souvla instead of ocakbaşi, Mythos in place of Efes, kalimera rather than merhaba.

One of the consequences of this long and varied history is that Kos has more than its fair share of archeological sites and spectacular ruins – you don’t have to travel far from one to explore the next. For the third time on this short trip, after Fethiye and Datça, we collect a rental car for a few days in order to take in the island, and there is much to see.

Mountains run down the spine of Kos, quaint bougainvillea splashed villages dot the hillsides, peace reigns supreme. In addition, there’s gushing cold water springs in the mountains and thermal springs pumping hot water into the sea as a result of past volcanic activity on nearby Nysiros. There are many more miles of sandy beach than most Greek islands can lay claim to, too. Some of these beach towns are weird places in November: there is absolutely nothing left. Not only is everything closed down and boarded up for winter, but, because these are ersatz villages catering for in-season vacationers, they are devoid of permanent population. There is, literally, nobody here in these strange temporary locations, probably not until pre-season preening time arrives. Tigaki, which looks every inch a lovely holiday destination, is the ghostliest of the ghost towns. After the gold rush, indeed.

Just along the coast from Kefalos, the lengthy expanse of sand known as Paradise Beach does its best to live up to its name – of course it’s quiet now with just a handful of people dotted along its length, but its calm beauty is undeniable. In hot summer sun this place must genuinely be a little piece of paradise. Even now we’re tempted to take a dip in its clear waters, maybe we’ll make a return if the weather plays ball.

It’s near Paradise Beach that we first hear it. Somewhere inside the closed down restaurant, there is a continuous, repetitive miaowing which is both drawling and plaintive. Somewhere in this rambling, empty building, a cat is in distress. Animal lovers – and particularly in my case cat lovers – that we are, we can’t leave without seeing what we can do to help. Eventually I find him, cowering beneath large leaves, miaowing over and over again and barely taking a breath. But he seems fine – his coat is silky, he is walking OK, he lets me pick him up and caress him. We can’t understand the reason for his distress. Then suddenly Michaela remembers a similar tale from her childhood. “I think he’s deaf”, she says. I go behind him and clap my hands – no reaction. I make that hissing sound which cats hate – no reaction. Michaela is right, he’s deaf, and he doesn’t know he’s making all this noise. As we drive away, his eyes are fixed on me, his little mouth opening and closing with plaintive cries which only he can’t hear. And I’ve just left a little piece of my heart at Paradise Beach.

Our road trips also take in the remains of Antimachia castle, the attractive town of Kefalos with the remains of its clifftop fortress and the winding roads leading to the mountaintop village of Zia. Zia is also closed and nigh on deserted, save for a group of old ladies chatting over a wall. From this high level vantage point, the clear views across the rest of Kos and on to dozens of other islands and the Turkish mainland, make the drive to the top worth every minute.

Central to the island is the small town of Pyli, split into its newer and older halves, where it seems half the population is dressed in black and heading for the church from which bells chime slowly and solemnly. A village character has clearly passed away. Unable to take what would be intrusive photographs of the picturesque church, we wander instead around the fountains of the gushing spring, past quaint chapels and silent homes, to the modest village square where the taverna is being prepared to receive the mourners. As with all funerals, it’s starting to rain.

As we make our way around Kos the island, we can’t help but wonder what life is like for the islanders once the holidaymakers and the summer sun is gone. What do all the restauranteurs, chefs, barmen, boatmen etc all do in the winter? Michaela takes the opportunity to practice her Greek and ventures to ask a group of ladies precisely that question….how do you fill your time in winter?

“Easy”, says one, smiling, “we stay indoors and eat cake”.

More Of Kos, Then On To Kalymnos

A number of things changed on Kos between our arrival on Monday morning and the Saturday ferry to our next destination. For one, the dull grey start turned into some glorious sunny days with blue skies and temperatures in the low to mid 20s, interrupted by heavy downpours on the Wednesday but leaving us feeling that generally we have been lucky. And, as the weather improved and the weekend approached, cafes and coffee bars started to reopen – not so much the tourist restaurants along the seafront but the cosy sites within the town, seemingly having moved on to a seasonal Thursday-to-Sunday opening regime.

For our last day with the rental car we explore the remainder of the island, including a more in depth look at the interesting village of Pyli in the island’s centre. The newer village, with its attractive plaza and busy tavernas, nestles up against a main drag with grocery stores, bakers and butchers shops, all evidence that this is a permanent town rather than one of the stranger seasonal places on the coast. But there is a third layer to Pyli, and a bit of a mystical one, too.

A few kilometres away, and considerably higher up the mountain, is the site where the original Pyli used to be, a village which grew up around the 11th century castle whose remains stand boldly at the summit. Somewhere around 1830, for reasons not totally understood by historians, the population of Pyli moved out, headed downhill and started work on the new location. The general consensus is that a plague of some kind wiped out most of the people, though the nature or identity of the epidemic, if that’s what it was, remains a mystery. Today the walls of the former homes house just goats and sheep while the ancient stonework keeps the rest of the story to itself.

An all-day walking tour of Kos Town completes our time on the island – there are so many ancient sites tucked into the corners of Kos that a full day is a minimum requirement. The imposing castle on the waterfront is unfortunately closed for repairs of some kind, but with the Roman odeon, the ancient stadium and agora, and the Casa Romana among the remaining sites, there is still so much of interest.

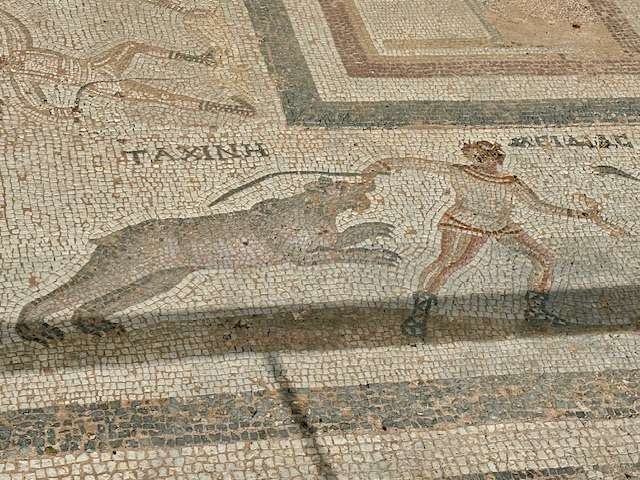

Casa Romana is an unusual place in that rather than leave the remaining walls at their ruined height, large parts of this impressive villa have been built up in modern times in order to recreate the full extent of the property. Not only does it achieve this, it also acts as protection from the elements for the wall art and fabulous floor mosaics which adorn the whole complex. This must have been home to some influential and prosperous people, most likely an island head in Hellenistic times.

Kos Town is a town full of oranges, in fact Kos is an island full of oranges. Streets are lined with fruit-laden trees, gardens across the island hang heavy with vivid orbs, fallers roll into gutters or get squashed by wheels. Either there’s a glut this year which far exceeds demand or it’s not harvest time yet, but whatever, there’s oranges all over the place. Or they might be tangerines.

Saturday morning. We’re at the ferry port far too early, there’s only three other passengers here, no port staff and no activity, but the morning sun is warm and there’s worse places to lose an hour than at a Greek island ferry port next to the blue Aegean. A moped rolls up. The other three passengers jump up, run to the moped, hand over cash and take delivery of coffee and pastries. They’ve ordered a takeaway breakfast for delivery to the dock. Now that’s what I call organised.

There’s something special, auspicious even, about arriving by boat into a welcoming port – a feeling which, no matter how many times we do it, is enhanced when it’s a Greek island. And oh wow does Kalymnos town aka Pothia tick every single one of those boxes, sweeping around its tightly curved crescent shaped bay and creeping as far as it dare up the barren mountainside. Windows reflect the morning sun in blinding rectangles, smells of baking drift from town to harbour, our smiling hosts are waving to us from the apartment balcony. It just looks every inch the perfect island port town.

Kalymnos is the island of sponge divers, the island of octopus meatballs, the island of rock climbing – and, judging by our first stroll around town, the island of beautifully photogenic architecture. Neoclassical buildings with angular gables, majestic churches with spires and clock towers, tight and steep alley ways where houses snuggle up tight to escape the wind – even the older crumbling places simply ooze character. Flights of stone steps elevate the curious visitor from sea to mountain with giddy steepness.

Soon enough after our arrival the puffer jackets and heavy coats of the Turks and Greeks are well justified – the Meltemi wind has overnight assumed its winter character and sends a biting straight-off-the-sea chill which seems to pass right through the rib cage. The sun teases with a pleasant warmth but the bite of Meltemi is winning, in the wind tunnels of the narrow streets and in shady corners, standing still is not an option. Flags stretch out in full, awnings rattle and leaves swirl in crazy dances. The cats of Kalymnos find the sunnier spots out of harm’s way and squat on their haunches. Felines aren’t stupid.

“Finally”, says the waitress as she delivers the beers, “winter is here. He is late this year”.

She may be right, although this is an Aegean winter and not a winter which delivers frost or snow, but rather one in which the sun is still beautiful, the sea is still a fabulous shade of blue, one where our faces can still catch a tan despite the puffer jackets and sweatshirts. As long as we hide from Meltemi.

Kalymnos: Diving For Sponge And The Joy Of Meze

Skevos is clearly pleased to see us or, more accurately, pleased to see someone, anyone, because being a museum curator out of season can be a lonely job. He has a face which carries a natural smile which is completely disarming in its sincerity. His full head of cascading white hair is long enough to sit neatly on the shoulders of his zipper jacket, nestling on the collar in the style of a rock band lead singer still strutting his stuff in the bars of Pothia. But he’s not here to sing, he’s here to tell us about sponge diving.

Sponge diving museum

He does so in articulate English and with a passion which betrays a family history in this most dangerous, daring of trades. Such is his enthusiasm that he regularly interrupts the introductory video to explain finer points in greater detail, putting the show on pause and swapping recorded narrative for passionate insight. The guy is magnetic and captivating, bringing this astonishing story to life as we hang on his every word.

The life of a sponge diver was one of continuously dicing with death in more ways than you can imagine. Paralysis brought on by “the bends”, death through accident, attacks by sharks and stingrays were the principal fears, but in addition to the ever present danger it was surely a life of misery too – each sortie was a trip of 6-7 months’ duration, working seven days a week, performing three dives per day. That’s around 600 dives per shift, away from home for half of each year, in places as distant as the North Africa coast.

So primitive was the equipment used that we continually gasp at what Skevos tells us: a slab of marble carried by the diver to ensure he was heavy enough to reach the seabed, incredibly basic breathing equipment, diving to depths of over 70 metres and staying down for 35 minutes on each of the three dives per day. And how was the 35 minutes measured in order to avoid death? By a fellow diver on the boat turning a basic egg timer 11 times and calling out when time was up.

So many other facts just bring home the horrors and dangers of the life of a sponge diver. Here’s a few. The 7 months’ salary was paid to the divers’ wives before the trip commenced, such was the likelihood that they wouldn’t all return. Up front payment put enormous pressure on the divers to succeed in their quest and captains were brutal in their demands, to the point that human life was an expendable collateral. The tiny boat had no facilities – seven months in open sun and salt water with no washing facilities; food taken at the outset which by the end is six months old; cooking water stored in containers which had previously carried petrol; no toilets, no beds, food rationed to one small meal each evening. All on top of the incredibly dangerous job.

One last thing. In the modern era, surfacing from such depths requires a minimum 32 minutes to avoid “the bends”. To maximise diving time and switch from one diver to the next, these guys were brought up in 4 (four!!) minutes. Fatalities were common, crippling and paralysis equally so. Few lived beyond 40.

Sponges though were lucrative business. Divers received around five times the pay of fishermen or mechanics, while boat captains, traders and exporters acquired substantial wealth – so much so that right up to today, Kalymnos is considered to be one of the better off of the Greek islands. Amongst the beautiful buildings of Pothia, some sponge shops remain, though not many, natural sponge having been mostly replaced by synthetic products. Those sponges which still hit the market are nowadays gathered by the island’s fishing fleet in, of course, a substantially safer environment.

And Pothia’s architecture is indeed an absolute delight, Neoclassical buildings with angular gables, majestic churches with spires and clock towers, Italianate design, characterful tight streets with proudly renovated town houses rubbing shoulders with crumbling properties which just ooze personality.

Away from Pothia, Kalymnos is a largely barren island dominated by soaring rocky mountains with little or no topsoil, indeed the canyons running inland from Pothia and Vathy are the only truly fertile areas. Driving the island is not an easy exercise – roads away from the towns are twisting affairs rich with tight hairpins, whereas roads through all towns and villages, Pothia included, are tight streets barely wide enough for anything more than a standard car yet filled with parked vehicles and carelessly abandoned mopeds.

The magnificent monastery of St Savvas looks down on Pothia from on high, castles, monasteries and ruins are tucked into many of the mountainsides, but probably our most thrilling call is at the cave church of Kyra Psili. Getting there isn’t easy, a hair raising drive up an unprotected track clinging to the escarpment is followed by an equally precipitous upward hike where loose stones, steep drops and the buffeting Meltemi wind do their best to send us back.

Saint Savvas, Kalymnos

But we persevere and it is so worth it, the tiny chapels chiselled into rocky caves, silent and miles from civilisation, constitute an eerie and mysterious place behind a heavy door tied shut with rope. Remote chapels created out of deep faith or from divine inspiration are always places full of deep mystery and a strong “presence”, and Kyra Psili is certainly no exception.

Pothia is a delightful looking town, kind of creating the picture perfect image of a Greek island port town, and now in late November much livelier than Kos, maybe evidence of the suggestion that Kalymnos people are generally a little better off than most other islanders. The Meltemi wind continues to power through but it’s not deterring the people of Pothia who happily fill the bars and cafes, wrapped up against the cold.

This onset of colder weather brings a huge benefit though in the quality of light, everything is so beautifully clear. Summits of mountains are crisply defined against the blue sky, the horizon is a perfect sharp line and the rocky slopes of the mountains themselves are beautifully framed in the crystal clear air.

We can’t leave Kalymnos without mentioning the food – this is surely Greek cuisine at its best. Because ouzo and tsipouro places dominate, the emphasis is on meze rather than large meals, and the result is a fabulous opportunity to try a whole range of different treats from unusual seafood (eg octopus meatballs, sea urchin roe) to sumptuously fresh veg dishes, fish straight from the boat and of course the ubiquitous souvlaki. The staple salad here is not the usual Greek salad either, but instead one named mermizeli, with soft cheese and crispy rusks in the mix – rusks which, just to take things from delicious to sublime, are laced with fennel.

Kalymnos has been delightful, Pothia doubly so. One of those rare places to which we would happily return.